Government borrowing hit a new high in December, driven by the cost of supporting households with their energy bills and rising debt interest costs.

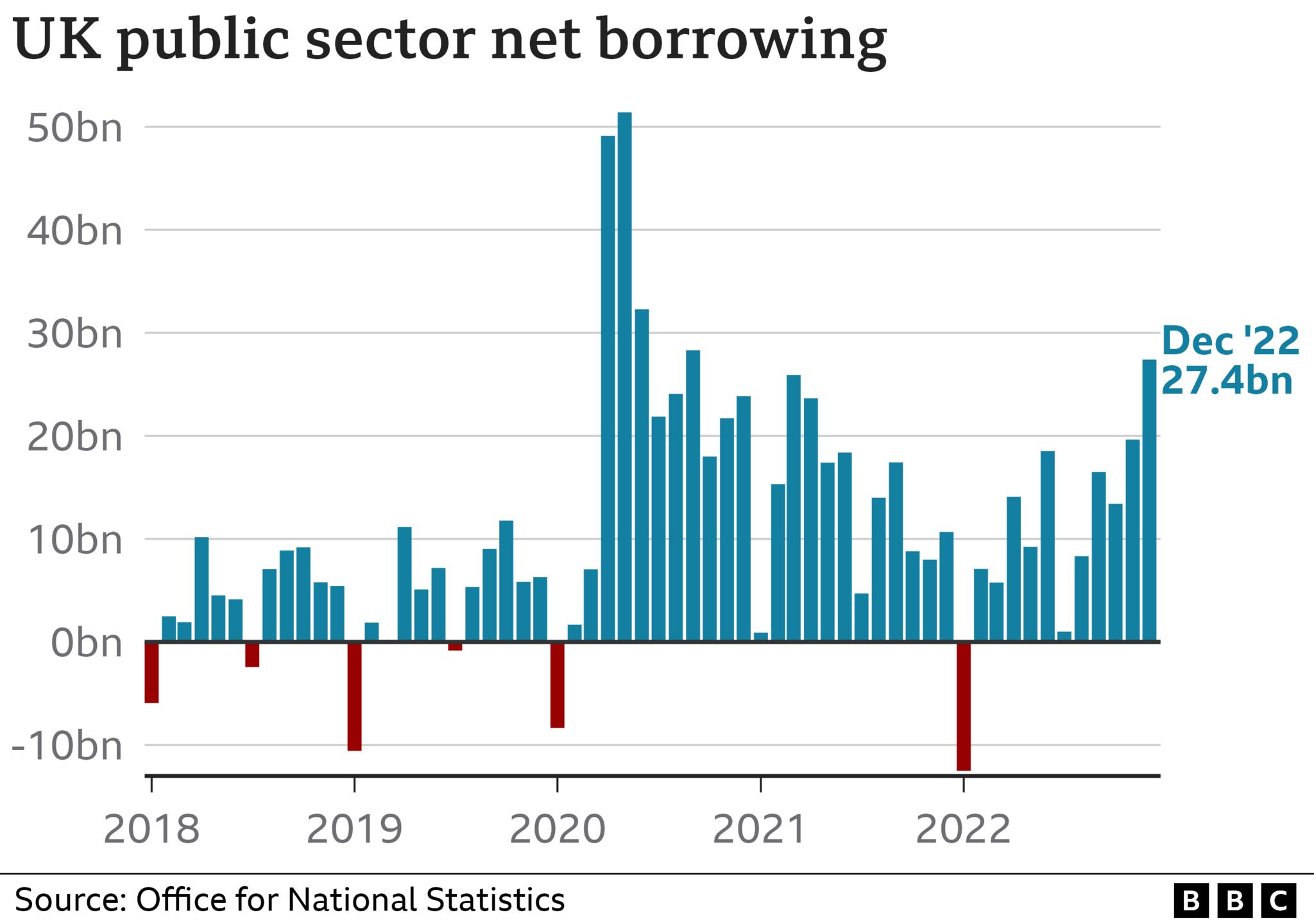

Borrowing, the difference between spending and tax income, was £27.4bn, the most for any December since records began in 1993.

Interest on government debt hit £17.3bn, more than doubling in a year.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) said inflation was the main factor behind the rise in borrowing.

While gas prices have begun to come down, the typical UK energy bill is still almost twice what it was before Russia invaded Ukraine.

To help ease the burden, the government cut energy bills in England, Scotland and Wales by £400 this winter.

It also launched the Energy Price Guarantee scheme, which limits average household bills to £2,500 per year.

- What is the energy price cap and what will happen to bills?

- From where does the government borrow billions?

It comes as inflation, the rate at which prices rise, is at its highest level for 40 years, putting millions of households under pressure.

Grant Fitzner, chief economist at the ONS, told the BBC that the cost of energy bill support had added around £7bn to the December borrowing figures.

Meanwhile interest payable on UK gilts, or bonds, which the government sells to international investors to raise the money it needs, has risen sharply, he said. This is because many gilts are “index linked”, meaning the government’s repayments rise in line with the Retail Prices Index measure of inflation which is currently at double-digit levels.

“If you stripped those two factors out, then underlying public sector borrowing would have been lower than a year ago,” Mr Fitzner told the Today programme:

He said government borrowing was likely to fall once the energy support schemes were no longer needed and inflation – which is thought to have peaked – finally comes down.

‘Deteriorating fast’

But Ruth Gregory, senior UK economist at Capital Economics, said the borrowing figures “provided more evidence that the government’s fiscal position is deteriorating fast”.

She said borrowing was well above what economists had expected, debt interest payments were at an “eye-watering” level, government spending was high, and there were “pressures from the weakening economy”.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt has said he will have to make “eye watering” public spending cuts to get the public finances back on track.

He has also had to reverse swathes of unfunded tax cuts promised by his predecessor, Liz Truss, after her plans sparked panic on financial markets.

Commenting on the latest borrowing figures, Mr Hunt said the government was “helping millions of families with the cost of living, but we must also ensure that our level of debt is fair for future generations”.

He added that the government has “already taken some tough decisions to get debt falling” as it tries to halve inflation and boost economic growth.

‘Turned a corner’

The ONS said total public sector debt reached £2.5 trillion at the end of December, or around 99.5% of UK economic output, or gross domestic product (GDP) – a level last seen in the early 1960s.

December’s figure took borrowing to £128.1bn so far in the financial year to the end of March, £5.1bn more year-on-year.

Bank Governor Andrew Bailey said last week that inflation might have turned a corner after it fell in November and December, adding that it is “likely to fall rapidly” this year as energy prices fall.

However, Mr Bailey also warned that high rates of job vacancies meant employees were in a strong bargaining position for wage rises which could stop inflation falling as quickly.

At 10.5%, the annual pace of price rises is more than five times higher than the Bank’s 2% target at the moment.

Without two factors – the energy support schemes and higher debt interest – borrowing would have been lower, the ONS says.

That raises an interesting question: why, given that Retail Prices Index (RPI) inflation is a discredited statistic, does the government pay higher debt interest at RPI?

It’s consistently higher than the official measure targeted by the Bank of England – the Consumer Prices Index.

The surprising answer is that the government doesn’t, as you or I would, seek to find the cheapest interest rate it can.

Instead it’s issuing “gilts”, also known as bonds, to suit big investors such as private pension funds, whose payouts to customers are linked to RPI and therefore need an asset linked to it.

This is one of many reasons why when the government borrows, it’s very unlike the borrowing a household or business does.

-

Who will get £900 to help with energy bills?

-

9 January

-

-

How does government borrowing work?

-

2 hours ago

-